Animals of the Oak

- Breath

- Time

- Humans

- Memory

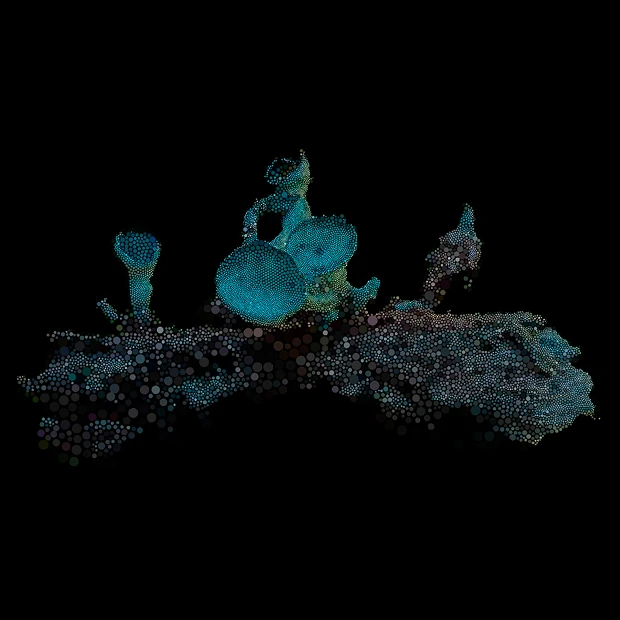

- Fungi

- Species

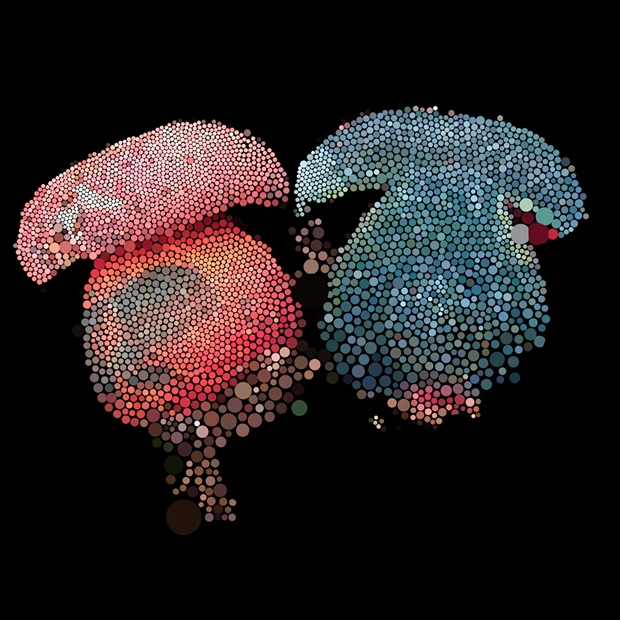

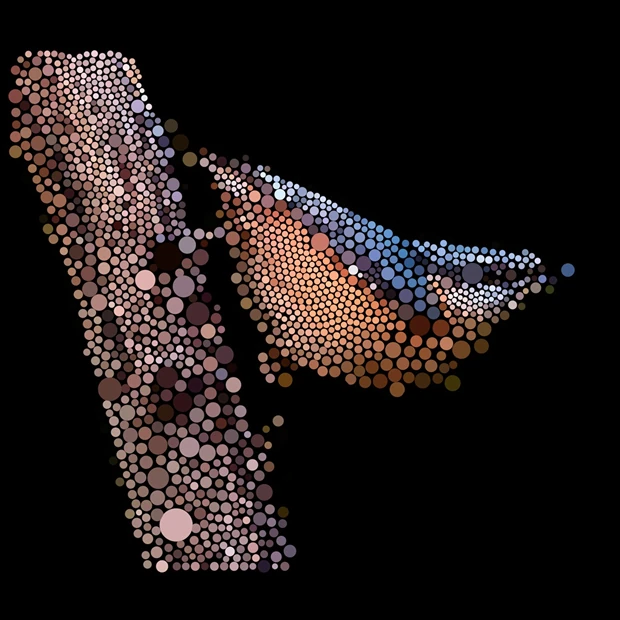

- Butterflies

Animals of the Oak

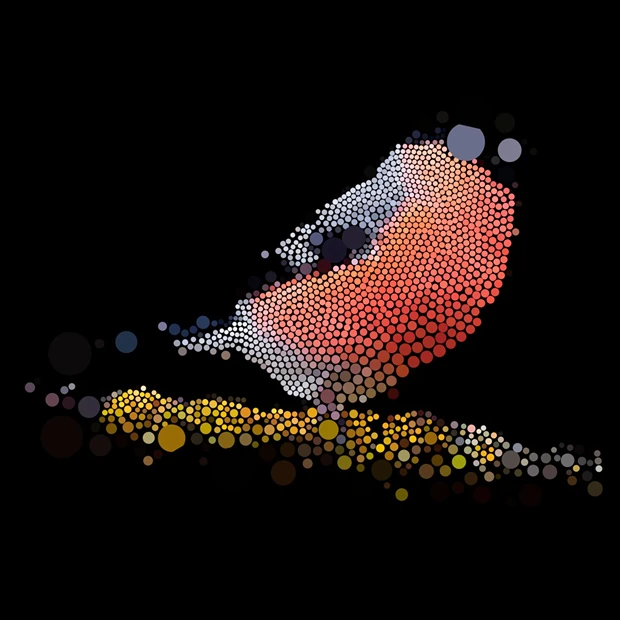

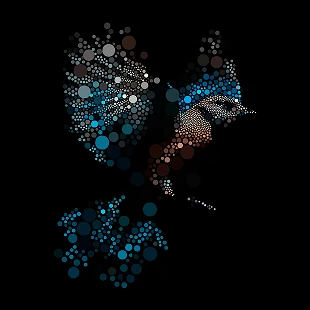

- Birds

- Dependants

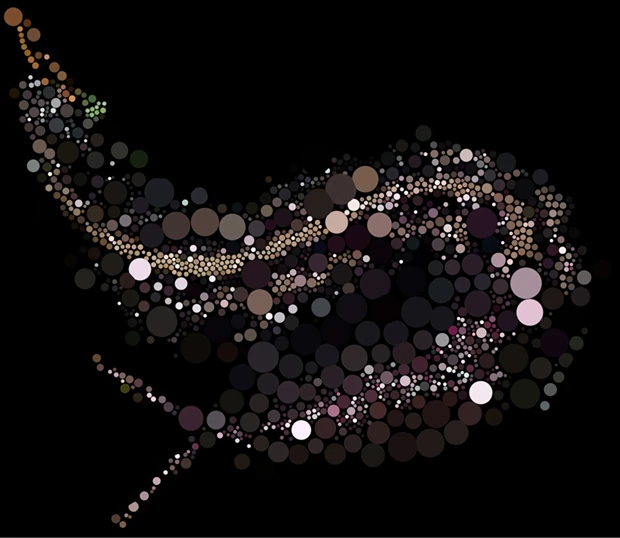

- Fungi

- Insects

- Soft Settlers

- Unlikely Inhabitants

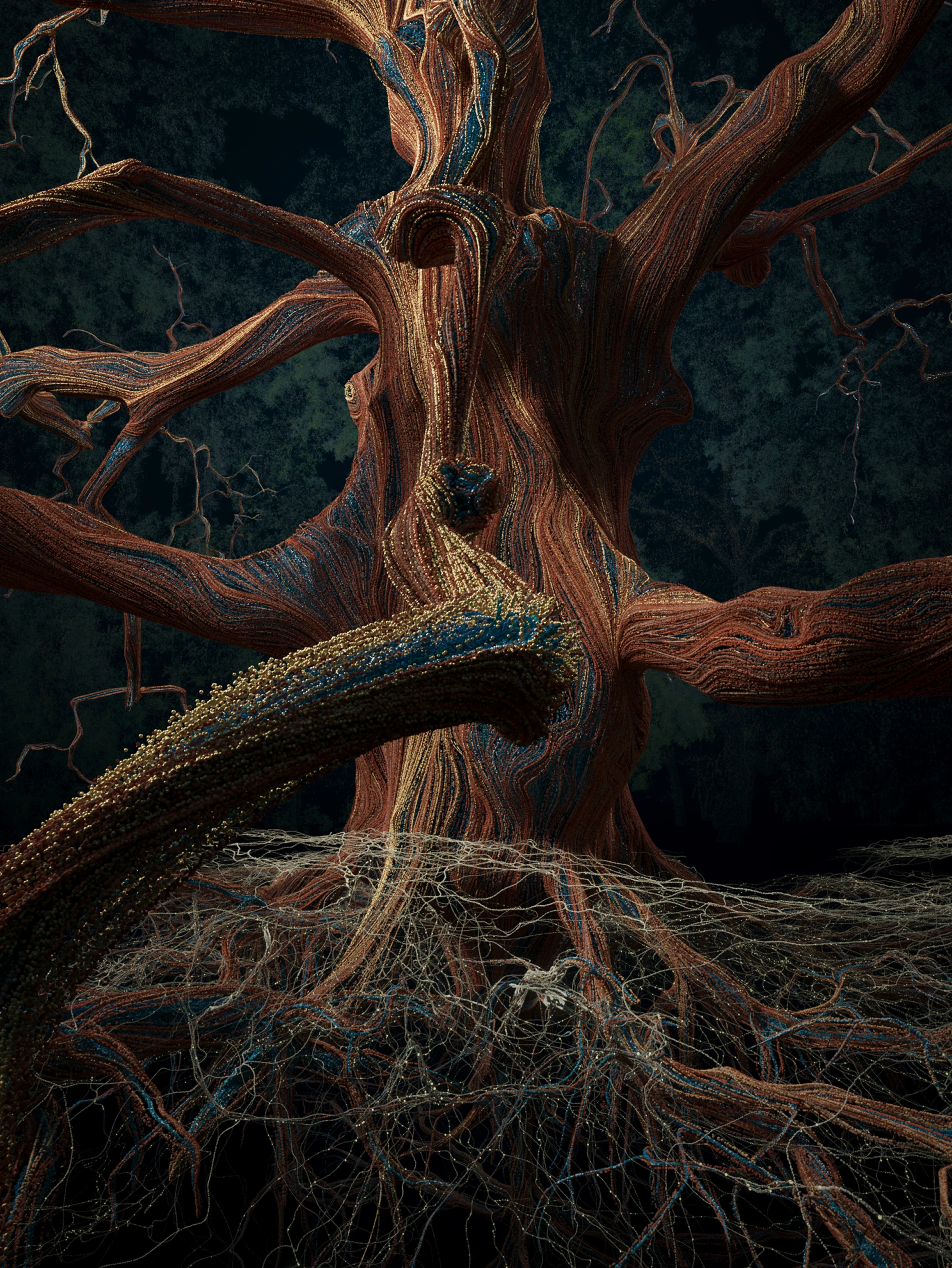

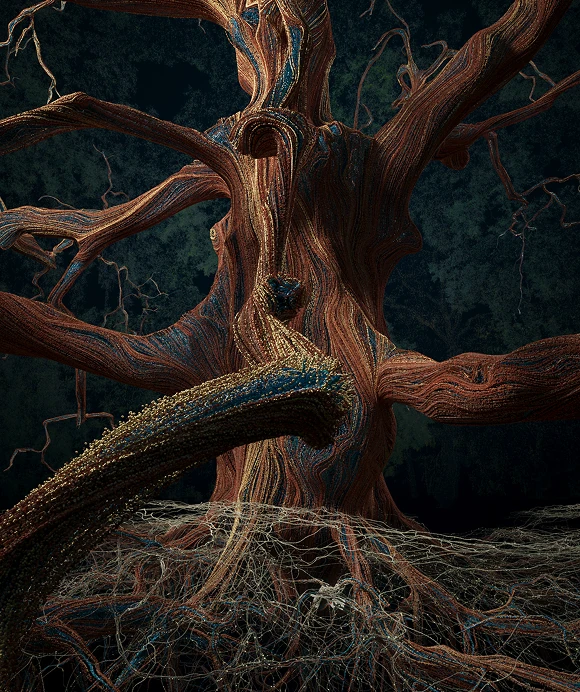

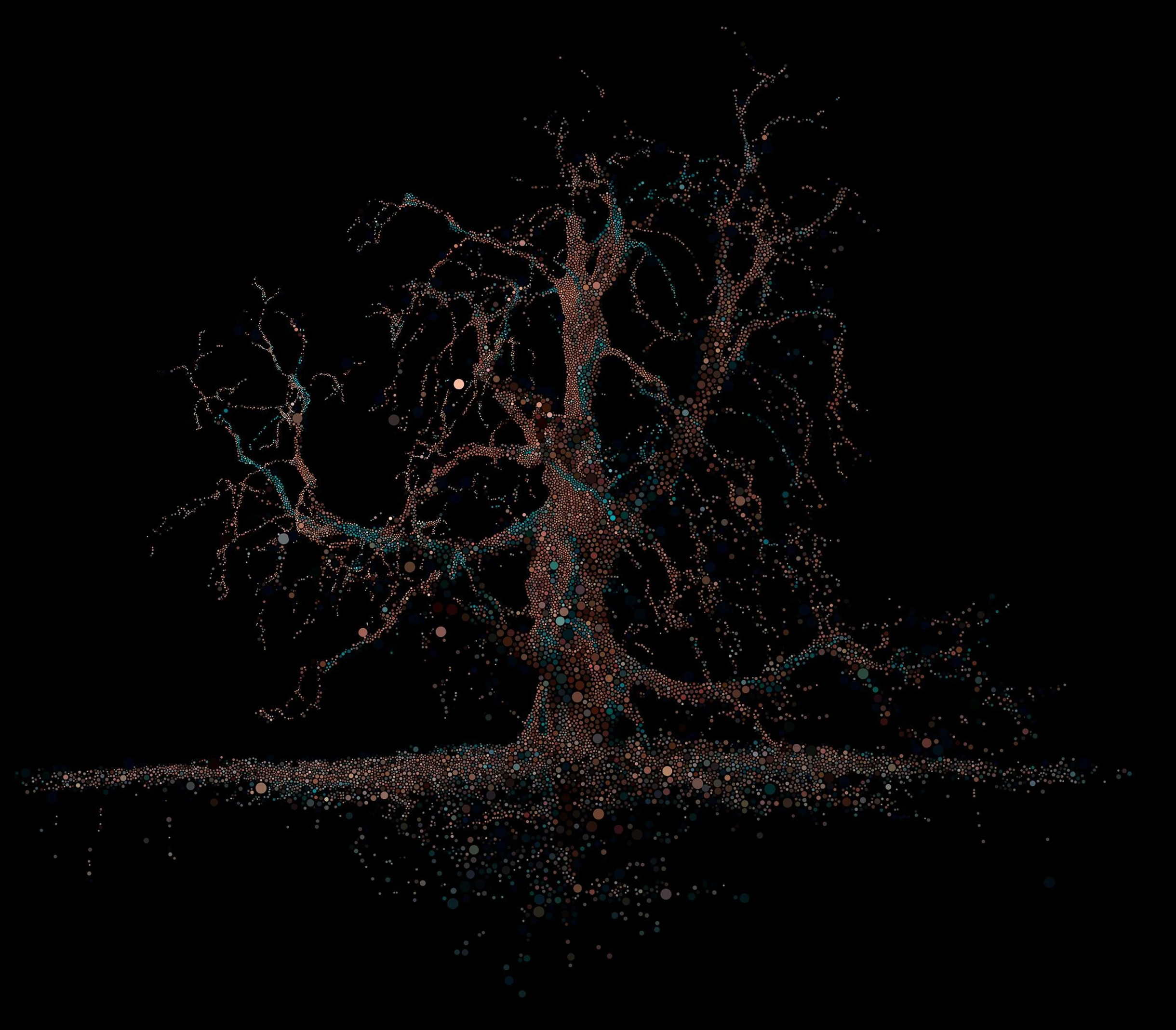

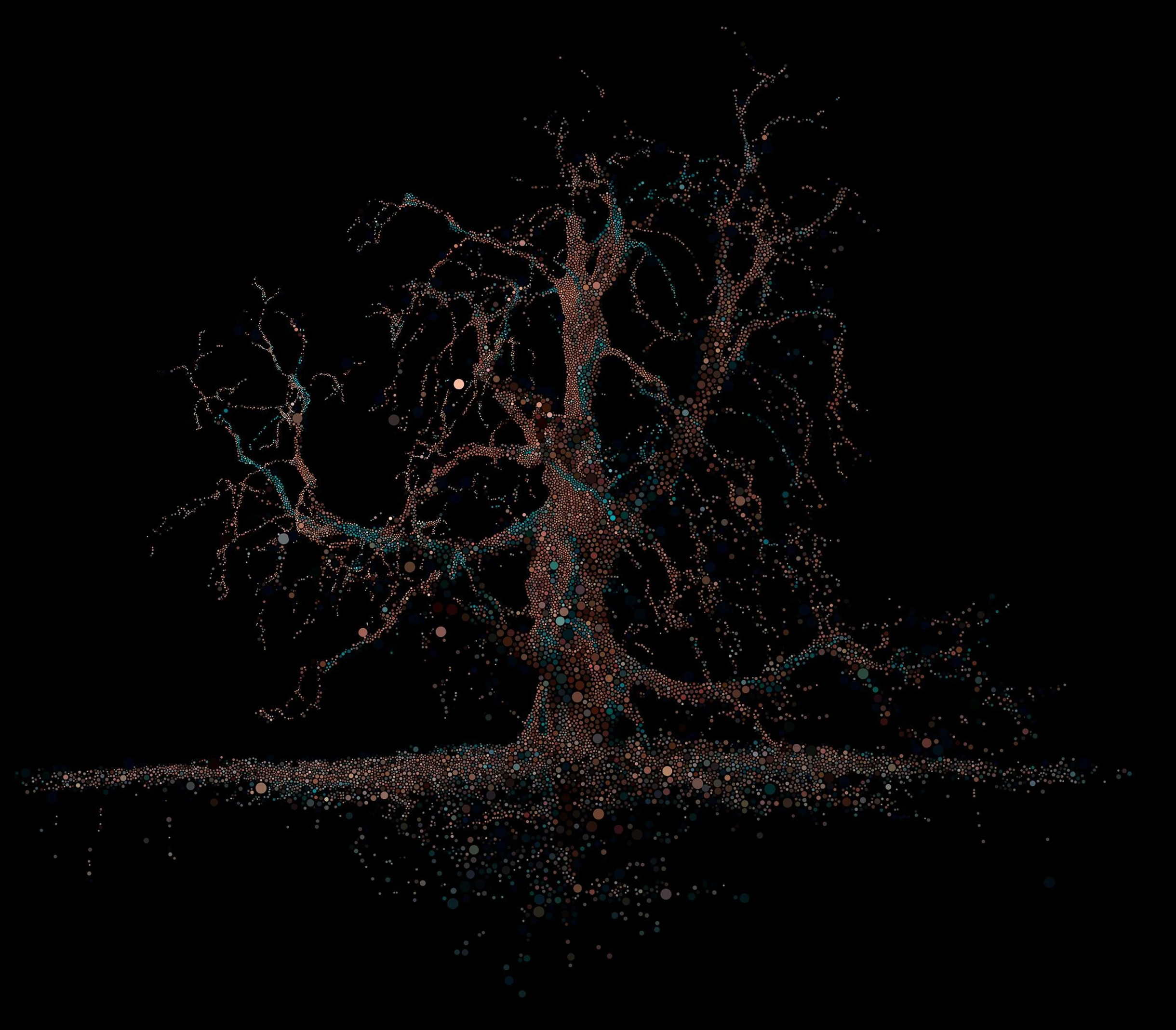

Of the oak A Journey Through Seasons and Species Of the Oak is Marshmallow Laser Feast’s inquiry into the hidden world of oak trees. Commissioned by the Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew, and created in collaboration with ecologists, biologists, and researchers, the project reveals the oak not merely as a tree, but as a living nexus of connection and reciprocity.

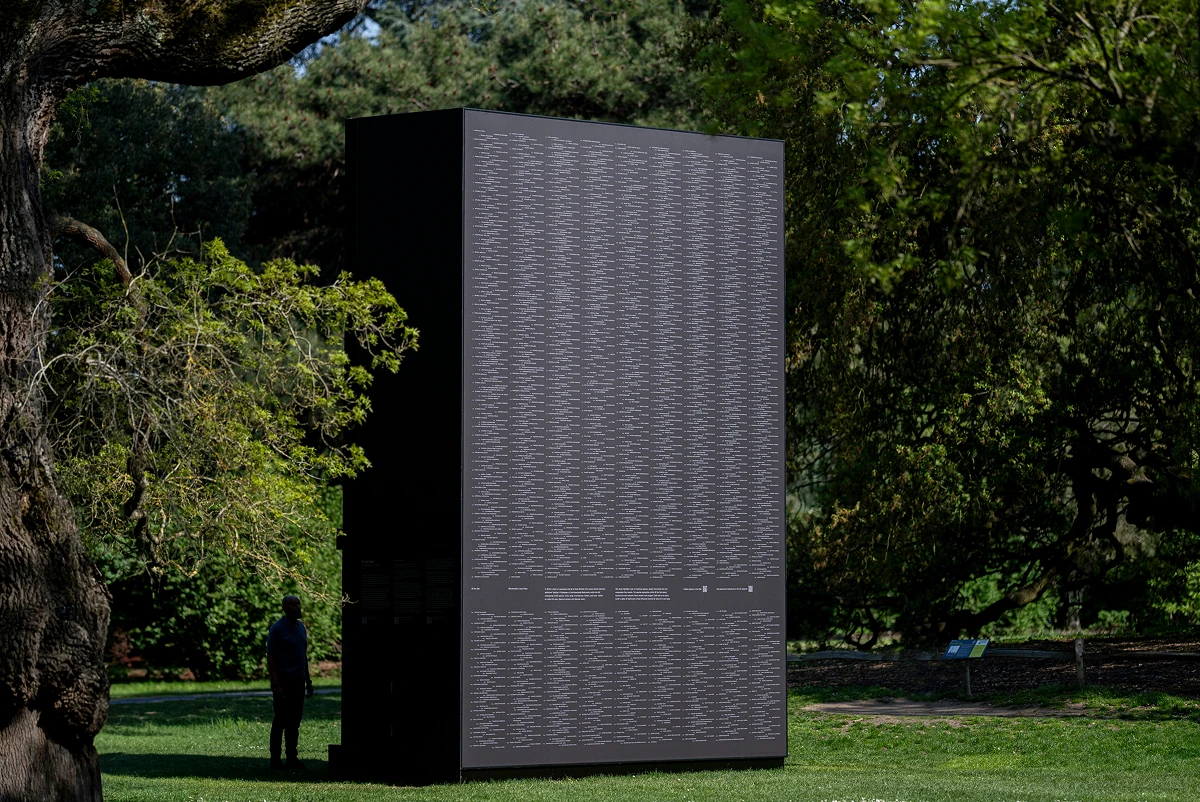

This immersive, multi-part artwork includes a large-scale site-specific video installation with multichannel audio, open-eyed meditations, and a web companion acting as a digital field guide to the oak’s symbiotic species. Together, they offer a sensory journey through the seasons, revealing the oak’s hidden vitality and its role in a complex web of life.

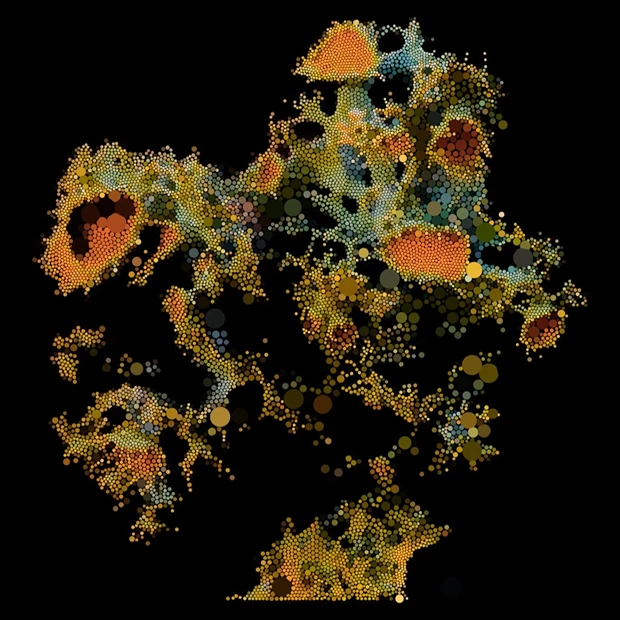

The web companion extends the project’s inquiry into the intricate, often invisible networks sustained by oak trees – mapping the species they support and their ecological interdependence.

The web companion extends the project’s inquiry into the intricate, often invisible networks sustained by oak trees – mapping the species they support and their ecological interdependence.  Alongside this ecological exploration, the companion features a series of open-eyed meditations authored by Daisy Lafarge, Merlin Sheldrake, Ella Saltmarshe and Laline Paull.

Alongside this ecological exploration, the companion features a series of open-eyed meditations authored by Daisy Lafarge, Merlin Sheldrake, Ella Saltmarshe and Laline Paull.  These texts offer poetic and contemplative entry points into the experience of being with trees, inviting moments of reflection grounded in both imagination and embodied attention.

These texts offer poetic and contemplative entry points into the experience of being with trees, inviting moments of reflection grounded in both imagination and embodied attention. Artist Statement  There is more to an oak than meets the eye.– A thread woven into the story of our kind.

There is more to an oak than meets the eye.– A thread woven into the story of our kind.

Of the Oak is an invitation to witness the tree as a living monument of connection, a keystone in the web of life. Majestic, yet unassuming, it reaches its branches skyward and roots deep into the soil, sustaining life.

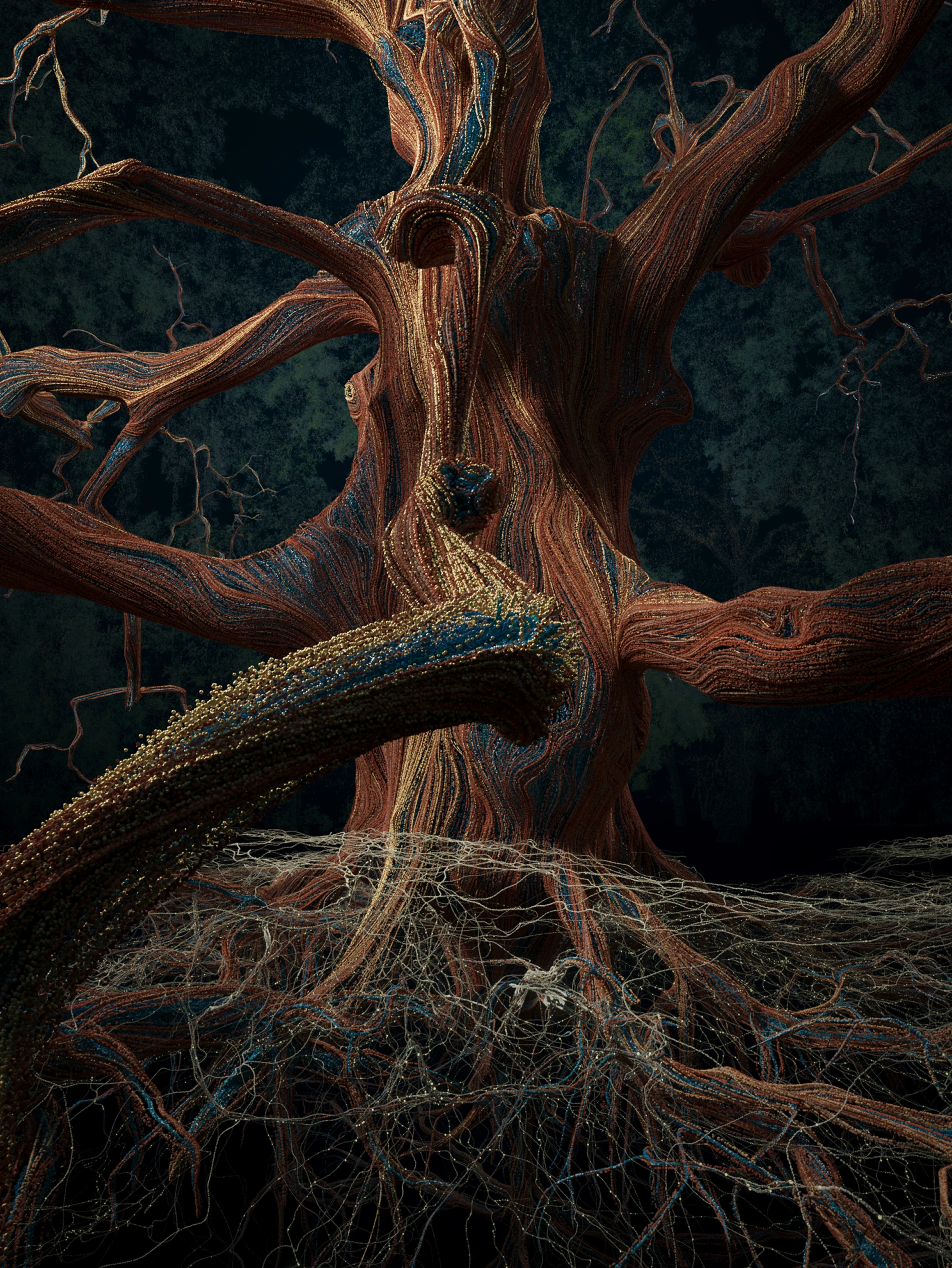

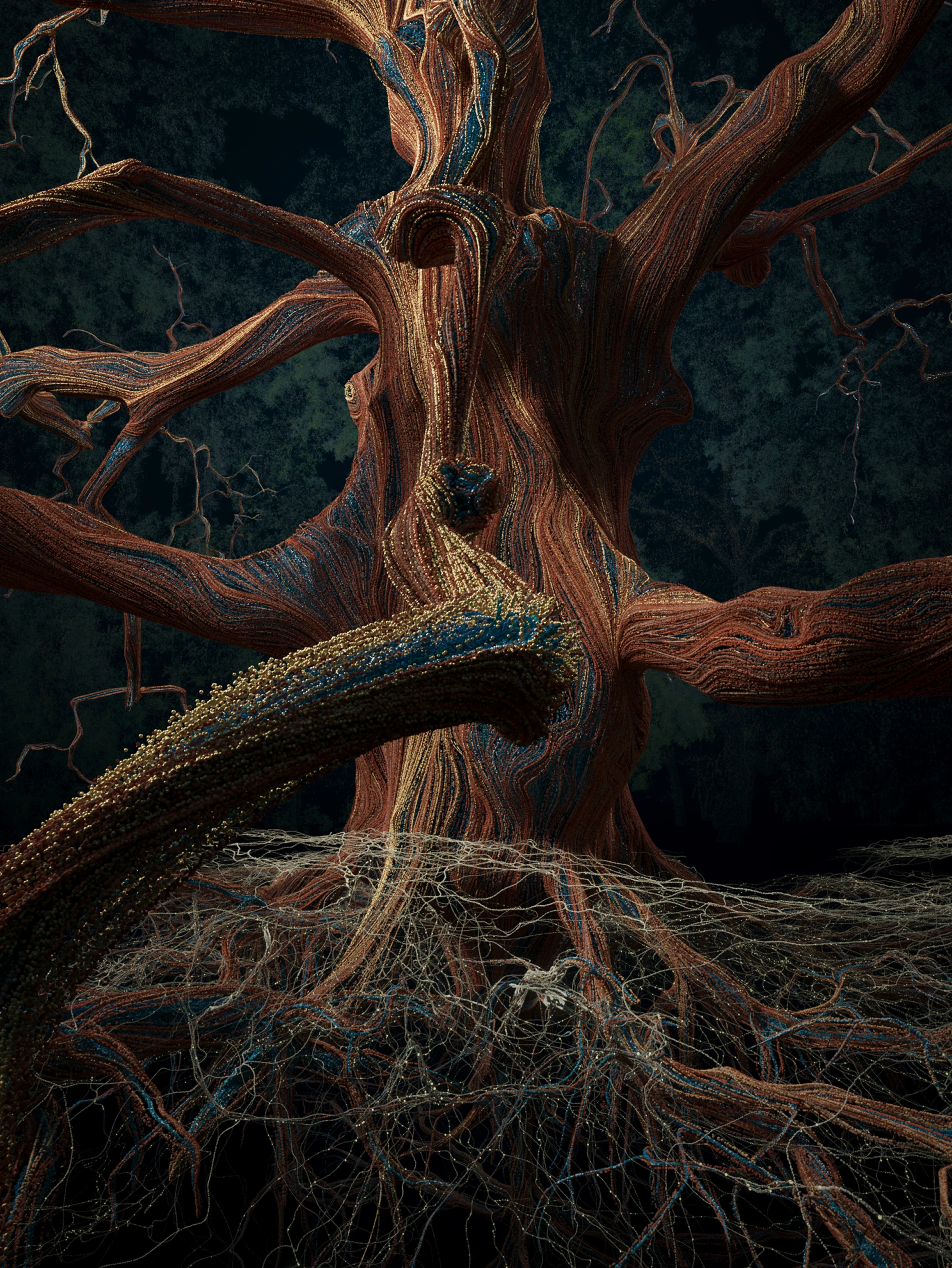

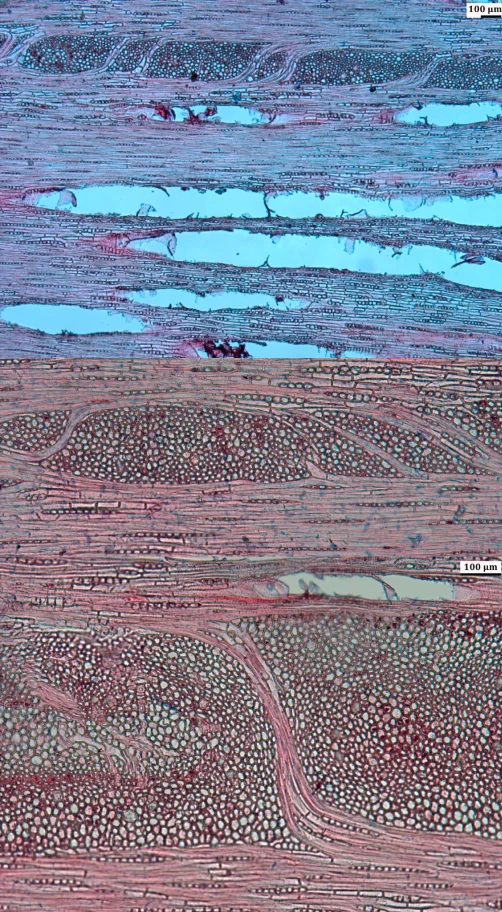

By peering through the oak's layers, we uncover a vibrancy that flows through and beyond its body. The pulse of nutrients through its phloem echoes our own heartbeat. This rhythmic journey, from crown to soil, culminates in rivers of carbon, interwoven with the mycelial bridge that connects land and sky. In this underground network, we see that no self is isolated; all are porous, enmeshed, entangled.

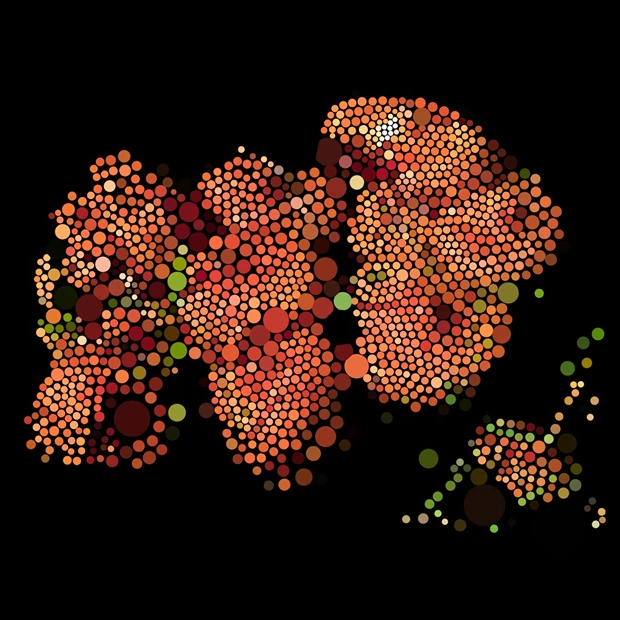

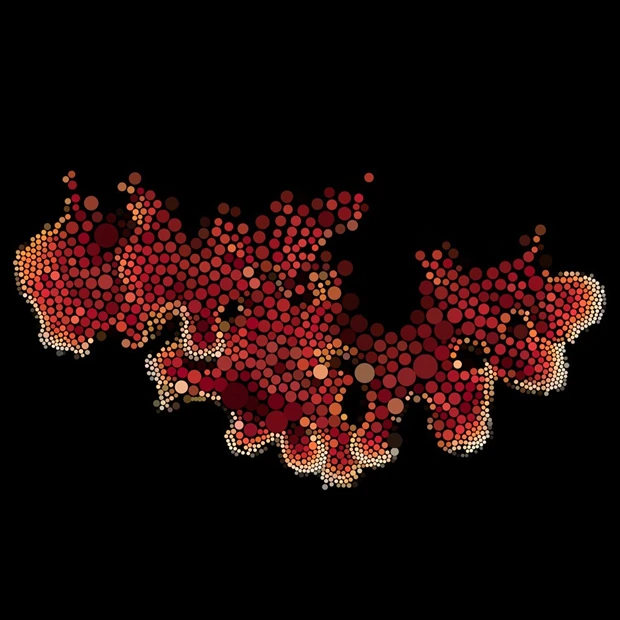

The oak's meaning stretches far beyond bark and bough. Its limbs embrace whole ecosystems, providing shelter and food for more than 2,300 species1. From lichens anchored to the bark to birds building nests overhead, butterflies fluttering through the leaves to fungi weaving the soil below – countless companions of the oak adapt, flourish, and coexist in a mutual rhythm of growth and revival. In acknowledging this complexity, we confront our own plant blindness, our tendency to overlook the aliveness of plants because they move to a rhythm slower than ours.

This shift in perspective reveals a framework of reciprocity, where all beings exist in cycles of giving and receiving. As our connection to the Earth frays, this work stands as an invitation to extend our imagination to include the vastness of trees. In turn, we also open ourselves to a deeper relationship with the living world.

For over a million years, oaks have taken root in Britain's soil, their story etched into the fabric of the land. As ice ages came and went, they withdrew and returned, reclaiming ground alongside animals and, eventually, humans. Yet today, these rooted beings stand at a threshold. What once seemed eternal now leans toward fragility, its fate entwined with our capacity to care. As we gather in its shade, we are called to become part of its story—to ensure it is not only remembered, but continued.

Marshmallow Laser Feast, 2025 Mitchell, R.J., et al. (2019). OakEcol: Oak-associated biodiversity in the UK.

There is more to an oak than meets the eye.– A thread woven into the story of our kind.

There is more to an oak than meets the eye.– A thread woven into the story of our kind.Of the Oak is an invitation to witness the tree as a living monument of connection, a keystone in the web of life. Majestic, yet unassuming, it reaches its branches skyward and roots deep into the soil, sustaining life.

By peering through the oak's layers, we uncover a vibrancy that flows through and beyond its body. The pulse of nutrients through its phloem echoes our own heartbeat. This rhythmic journey, from crown to soil, culminates in rivers of carbon, interwoven with the mycelial bridge that connects land and sky. In this underground network, we see that no self is isolated; all are porous, enmeshed, entangled.

The oak's meaning stretches far beyond bark and bough. Its limbs embrace whole ecosystems, providing shelter and food for more than 2,300 species1. From lichens anchored to the bark to birds building nests overhead, butterflies fluttering through the leaves to fungi weaving the soil below – countless companions of the oak adapt, flourish, and coexist in a mutual rhythm of growth and revival. In acknowledging this complexity, we confront our own plant blindness, our tendency to overlook the aliveness of plants because they move to a rhythm slower than ours.

This shift in perspective reveals a framework of reciprocity, where all beings exist in cycles of giving and receiving. As our connection to the Earth frays, this work stands as an invitation to extend our imagination to include the vastness of trees. In turn, we also open ourselves to a deeper relationship with the living world.

For over a million years, oaks have taken root in Britain's soil, their story etched into the fabric of the land. As ice ages came and went, they withdrew and returned, reclaiming ground alongside animals and, eventually, humans. Yet today, these rooted beings stand at a threshold. What once seemed eternal now leans toward fragility, its fate entwined with our capacity to care. As we gather in its shade, we are called to become part of its story—to ensure it is not only remembered, but continued.

Marshmallow Laser Feast, 2025 Mitchell, R.J., et al. (2019). OakEcol: Oak-associated biodiversity in the UK.

Environmental Impact of the artwork At Marshmallow Laser Feast, our practice is rooted in telling stories that deepen our relationship with the more-than-human world. We draw inspiration from the hidden life of ecosystems and find emotional and creative resonance in scientific research. For us, revealing the animism of nature – its vitality, complexity and interconnection – is not only an artistic pursuit, but a deeply felt responsibility.

Of the Oak invites viewers to see the oak tree not just as a static form, but as a living network – a vital node in a vast web of life. Yet while the work celebrates the intelligence and beauty of nature, we also recognise the inherent contradictions in using energy-intensive technologies to create and deliver that message. It's a tension we hold consciously: to speak of ecological urgency while acknowledging our own environmental footprint.

During the 242-day production period, approximately 7,100 kWh of energy was consumed – roughly equivalent to two years of electricity use for an average UK household. While this energy enabled us to visualise a hidden world for an audience that may never otherwise encounter it, we remain mindful of the cost. Transparency is important, and we've made a detailed breakdown of energy use available here.

The outdoor video installation runs at approximately 10 kW per hour and is powered using Kew Gardens' sustainable hard power infrastructure. The screen is responsive to its environment, and it powers down entirely outside of opening hours to minimise energy use.

We believe that opening up conversations about ecological interdependence, loss, and resilience is essential – and that immersive experiences, when done with care, can help catalyse those conversations. Over the course of the exhibition, more than half a million visitors will encounter Of the Oak. If even a fraction leave seeing trees – and the living world they uphold – with new eyes, then the energy spent begins to carry its own kind of value.

This work is not the final word, but part of a longer dialogue. As artists working at the intersection of ecology and technology, we are committed to continuing to evolve our practice—to reduce our impact, increase transparency, and explore new ways of telling stories that honour the world we depend on.

Of the Oak invites viewers to see the oak tree not just as a static form, but as a living network – a vital node in a vast web of life. Yet while the work celebrates the intelligence and beauty of nature, we also recognise the inherent contradictions in using energy-intensive technologies to create and deliver that message. It's a tension we hold consciously: to speak of ecological urgency while acknowledging our own environmental footprint.

During the 242-day production period, approximately 7,100 kWh of energy was consumed – roughly equivalent to two years of electricity use for an average UK household. While this energy enabled us to visualise a hidden world for an audience that may never otherwise encounter it, we remain mindful of the cost. Transparency is important, and we've made a detailed breakdown of energy use available here.

The outdoor video installation runs at approximately 10 kW per hour and is powered using Kew Gardens' sustainable hard power infrastructure. The screen is responsive to its environment, and it powers down entirely outside of opening hours to minimise energy use.

We believe that opening up conversations about ecological interdependence, loss, and resilience is essential – and that immersive experiences, when done with care, can help catalyse those conversations. Over the course of the exhibition, more than half a million visitors will encounter Of the Oak. If even a fraction leave seeing trees – and the living world they uphold – with new eyes, then the energy spent begins to carry its own kind of value.

This work is not the final word, but part of a longer dialogue. As artists working at the intersection of ecology and technology, we are committed to continuing to evolve our practice—to reduce our impact, increase transparency, and explore new ways of telling stories that honour the world we depend on.

And now you stand with your back to the oak, looking out at the spool of human history tangled and blossoming from its branches. Where would you be without it? All this time the oak stands still, a stillness has moved you further than you ever thought possible. And so you thrive: around and about and within its greening, making you a human of the oak. Daisy Lafarge, Excerpt from Humans of the Oak

A Portal into Nature's Hidden Web Creative Overview Quercus x hispanica

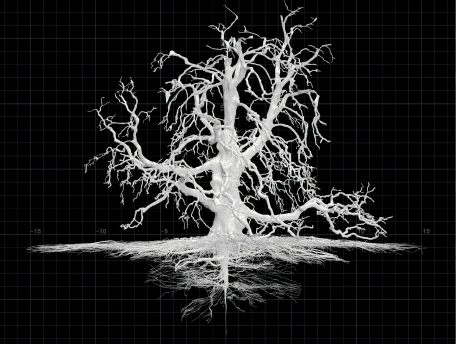

‘Lucombeana’ At the heart of the artwork stands the magnificent Lucombe Oak (Quercus × hispanica ‘Lucombeana’) – a rare hybrid first discovered in 1760. Chosen for its sweeping branches and intricate form, this iconic tree becomes the centrepiece of the experience.

At the heart of the artwork stands the magnificent Lucombe Oak (Quercus × hispanica ‘Lucombeana’) – a rare hybrid first discovered in 1760. Chosen for its sweeping branches and intricate form, this iconic tree becomes the centrepiece of the experience.

‘Lucombeana’

At the heart of the artwork stands the magnificent Lucombe Oak (Quercus × hispanica ‘Lucombeana’) – a rare hybrid first discovered in 1760. Chosen for its sweeping branches and intricate form, this iconic tree becomes the centrepiece of the experience.

At the heart of the artwork stands the magnificent Lucombe Oak (Quercus × hispanica ‘Lucombeana’) – a rare hybrid first discovered in 1760. Chosen for its sweeping branches and intricate form, this iconic tree becomes the centrepiece of the experience. William Barron's horse-powered Tree. Transplanter, purchased by Kew in 1866.  In 1762, on the outskirts of Exeter, two disparate beings – a Turkey oak (Quercus cerris) and an evergreen cork oak (Q. suber) – crossed paths and entwined, giving birth to a new hybrid: the Lucombe oak. This tree, grown from a cutting of that original hybrid, stands as one of the oldest of its kind – a living thread stretching back through centuries.

In 1762, on the outskirts of Exeter, two disparate beings – a Turkey oak (Quercus cerris) and an evergreen cork oak (Q. suber) – crossed paths and entwined, giving birth to a new hybrid: the Lucombe oak. This tree, grown from a cutting of that original hybrid, stands as one of the oldest of its kind – a living thread stretching back through centuries.

When landscape designer William Nesfield reimagined the Arboretum in 1845, the mature Lucombe Oak stood in the way of the pristine sightline of his newly conceived Syon Vista. Yet rather than be discarded, it was carefully uprooted and moved twenty metres to its current location — a quiet testament to resilience, adaptation, and the human instinct to preserve what is cherished.

We wanted to reimagine the artwork in its original location — where Of the Oak now stands.

Named after William Lucombe, the nurseryman who first cultivated it, the tree's story is laced with devotion. So deeply connected to the original oak, Lucombe had it felled and kept the wood beneath his bed, intending it to be crafted into his coffin – a gesture of kinship, longing for permanence, and a recognition of life's interwoven continuum.

In 1762, on the outskirts of Exeter, two disparate beings – a Turkey oak (Quercus cerris) and an evergreen cork oak (Q. suber) – crossed paths and entwined, giving birth to a new hybrid: the Lucombe oak. This tree, grown from a cutting of that original hybrid, stands as one of the oldest of its kind – a living thread stretching back through centuries.

In 1762, on the outskirts of Exeter, two disparate beings – a Turkey oak (Quercus cerris) and an evergreen cork oak (Q. suber) – crossed paths and entwined, giving birth to a new hybrid: the Lucombe oak. This tree, grown from a cutting of that original hybrid, stands as one of the oldest of its kind – a living thread stretching back through centuries.When landscape designer William Nesfield reimagined the Arboretum in 1845, the mature Lucombe Oak stood in the way of the pristine sightline of his newly conceived Syon Vista. Yet rather than be discarded, it was carefully uprooted and moved twenty metres to its current location — a quiet testament to resilience, adaptation, and the human instinct to preserve what is cherished.

We wanted to reimagine the artwork in its original location — where Of the Oak now stands.

Named after William Lucombe, the nurseryman who first cultivated it, the tree's story is laced with devotion. So deeply connected to the original oak, Lucombe had it felled and kept the wood beneath his bed, intending it to be crafted into his coffin – a gesture of kinship, longing for permanence, and a recognition of life's interwoven continuum.

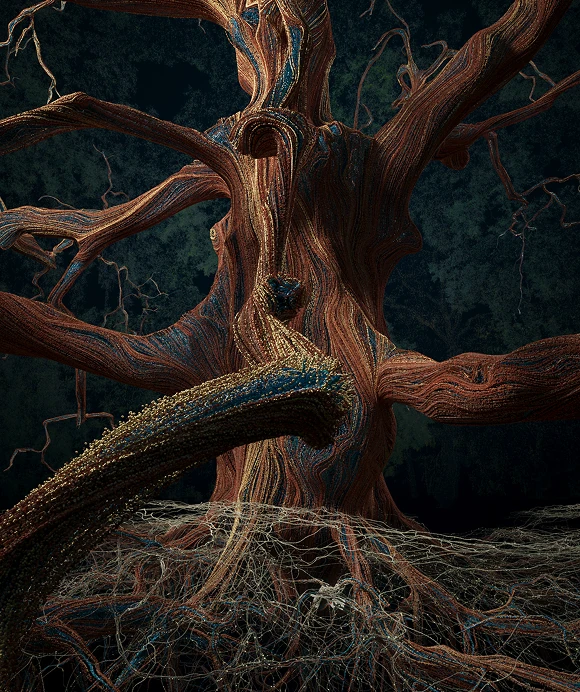

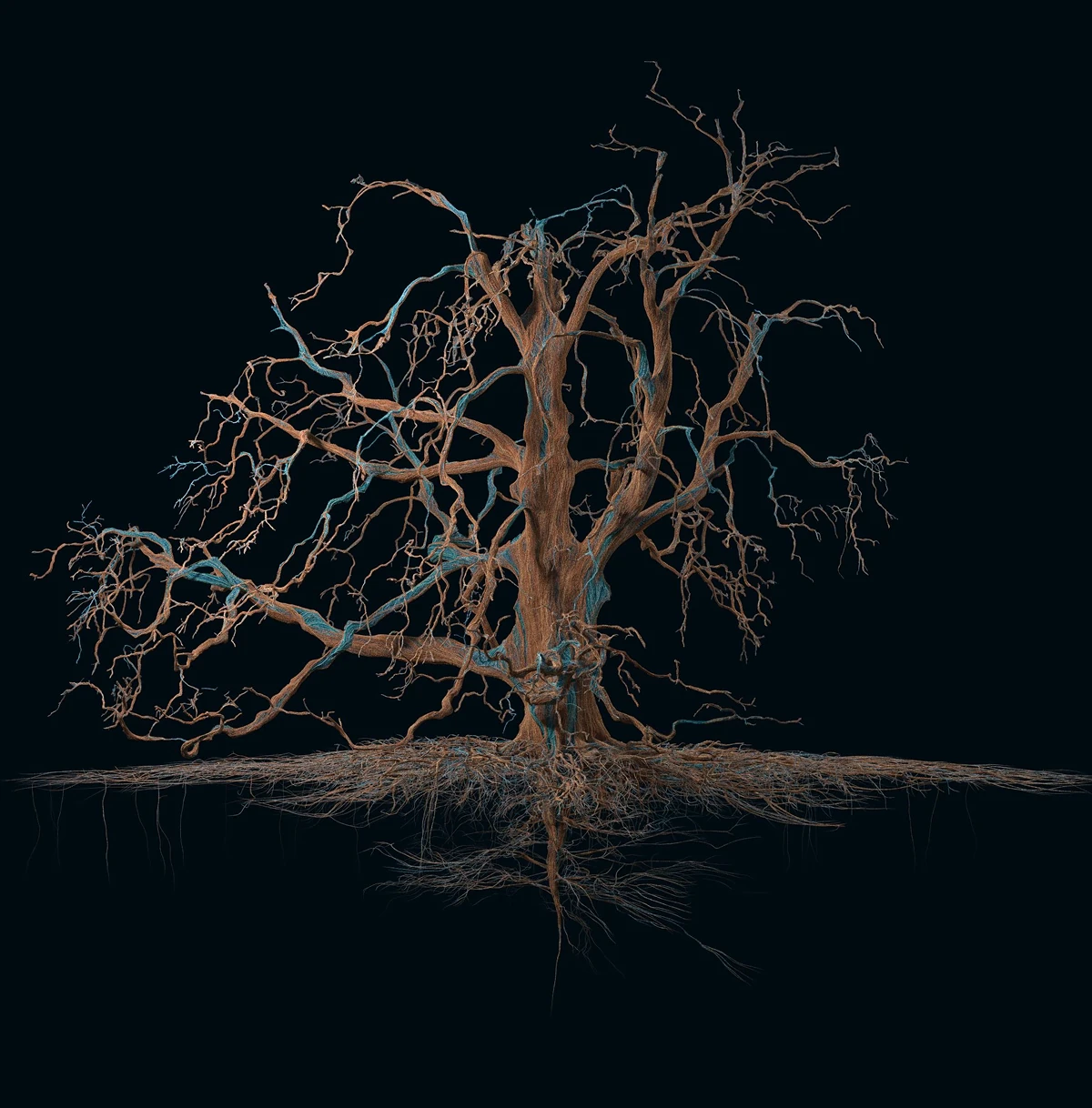

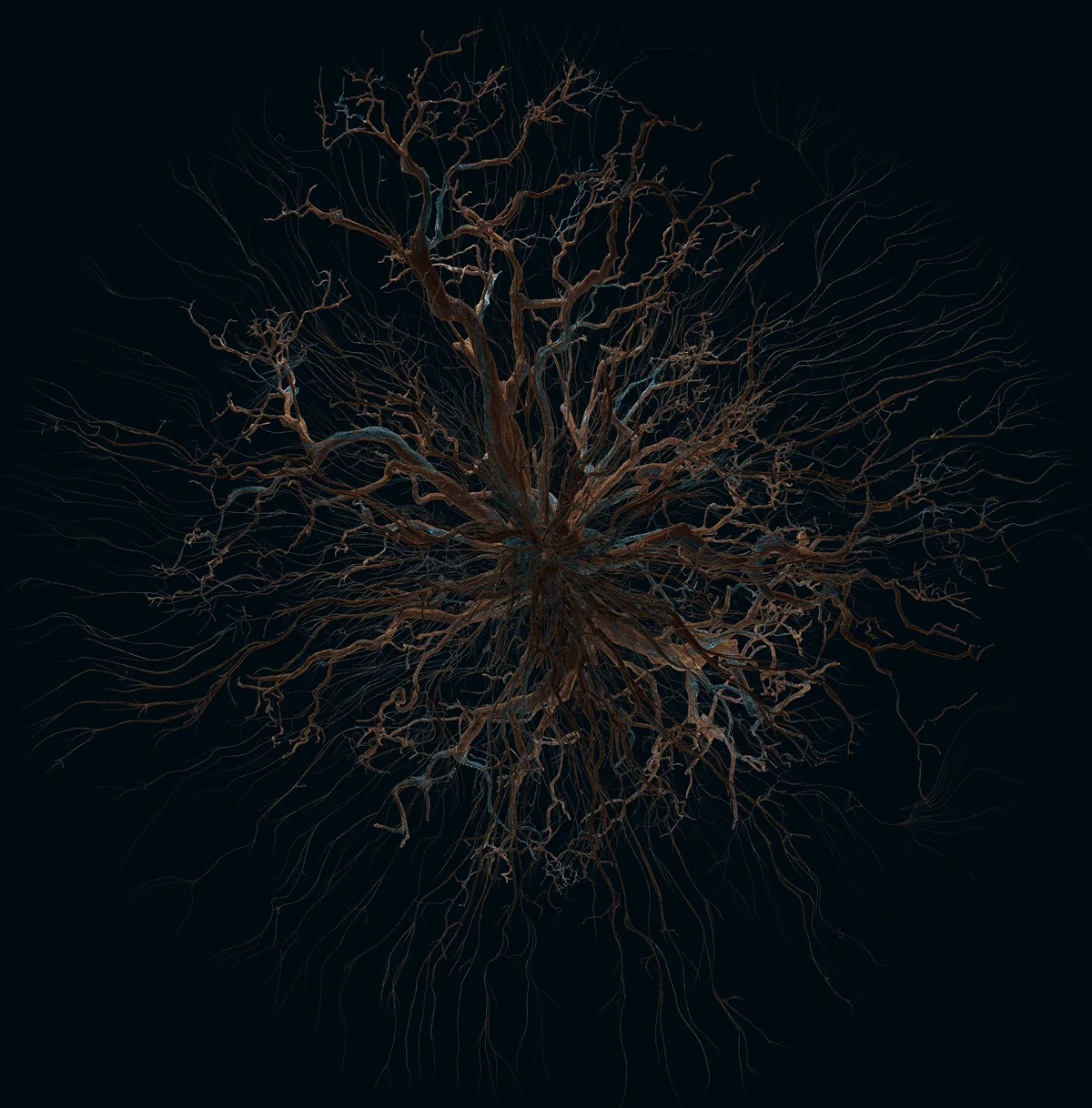

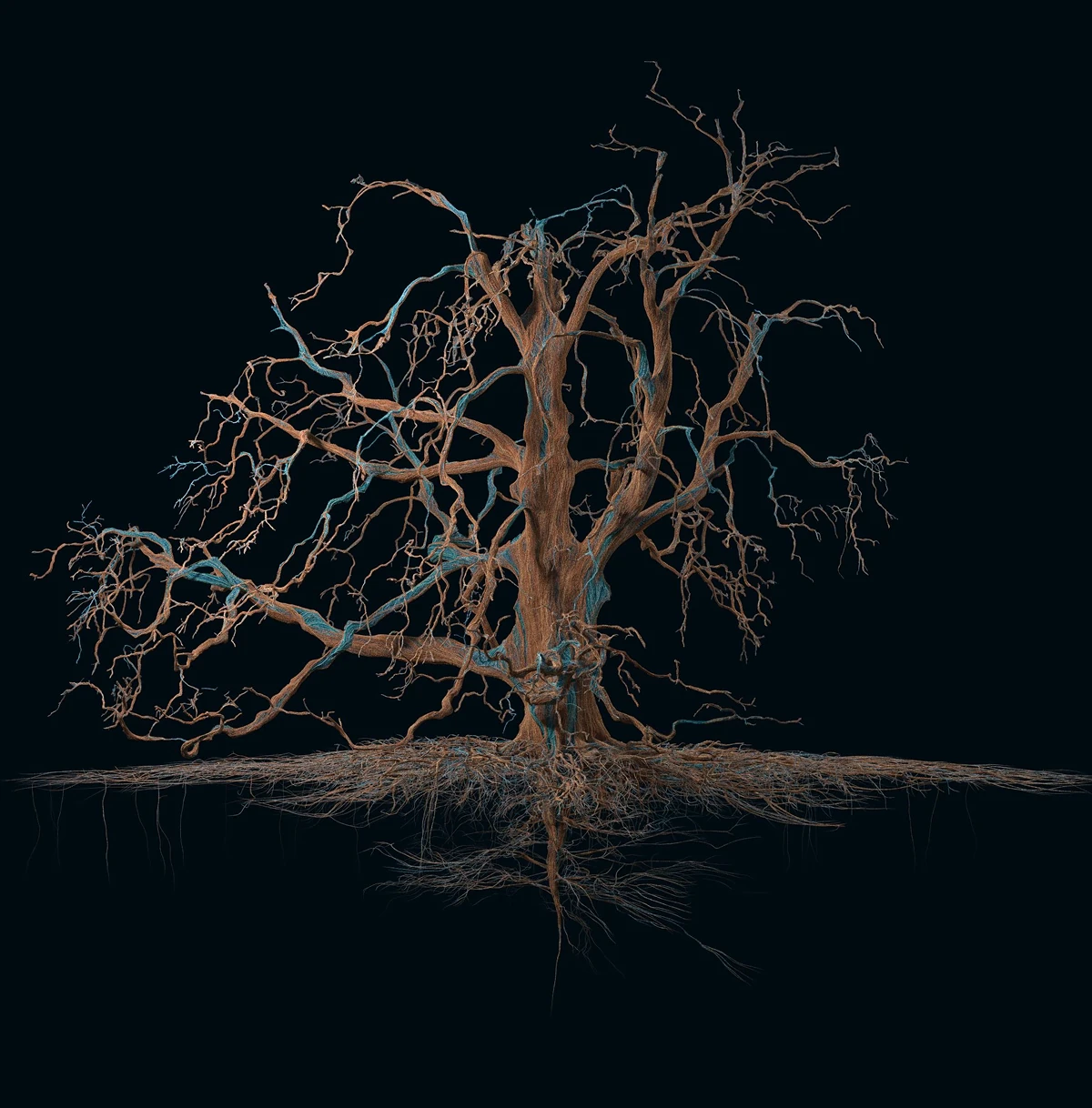

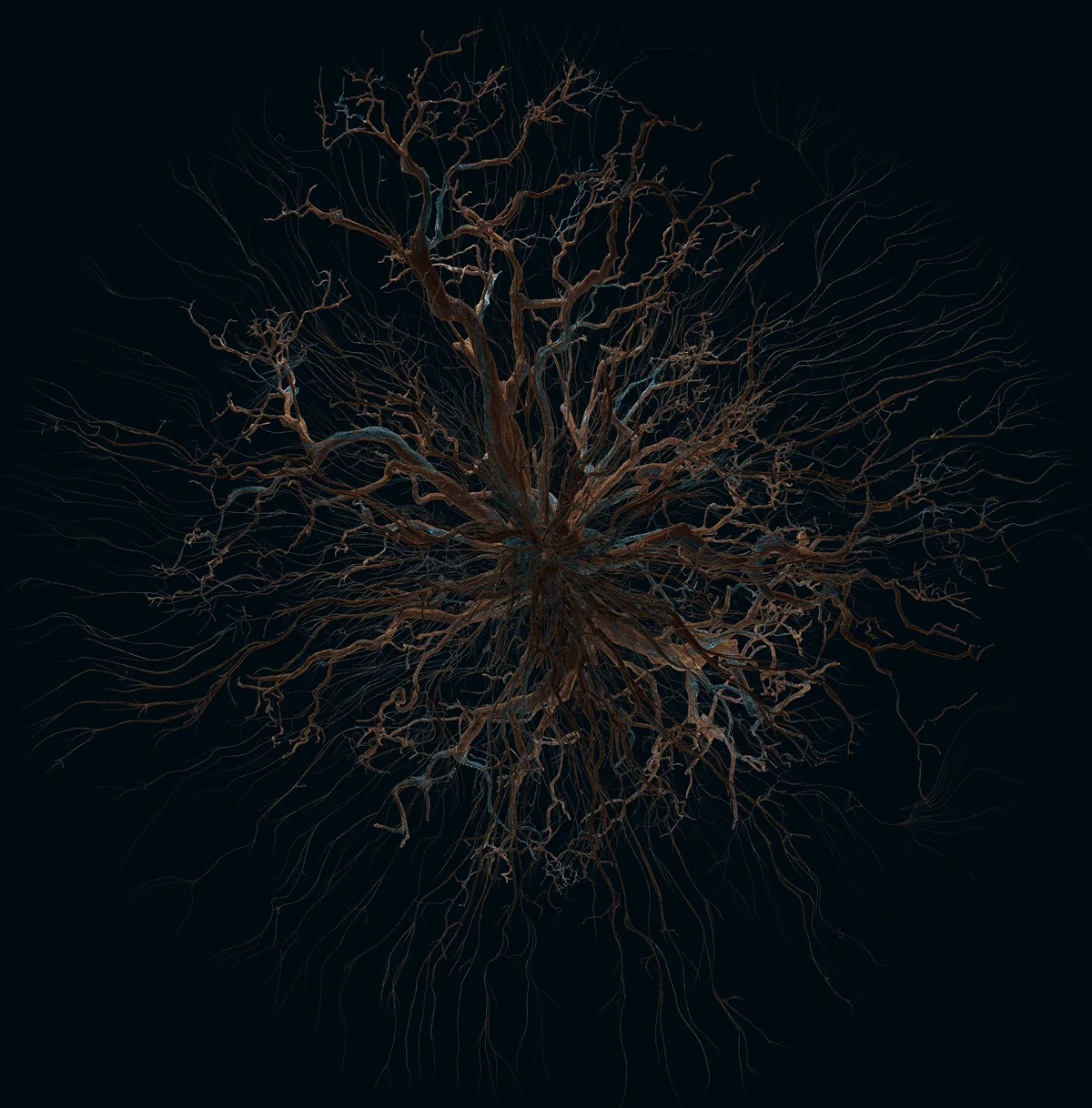

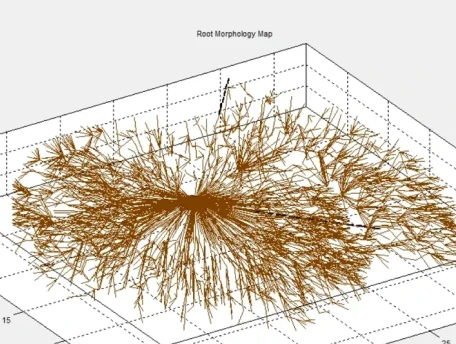

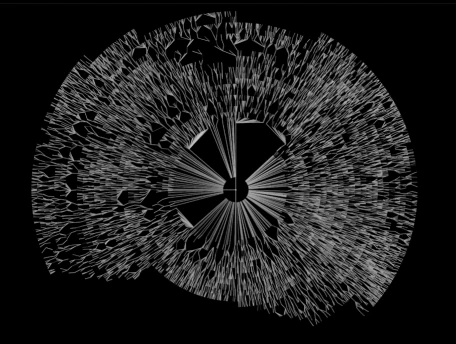

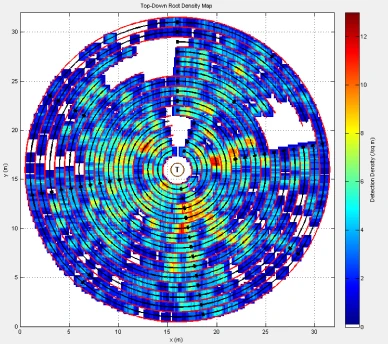

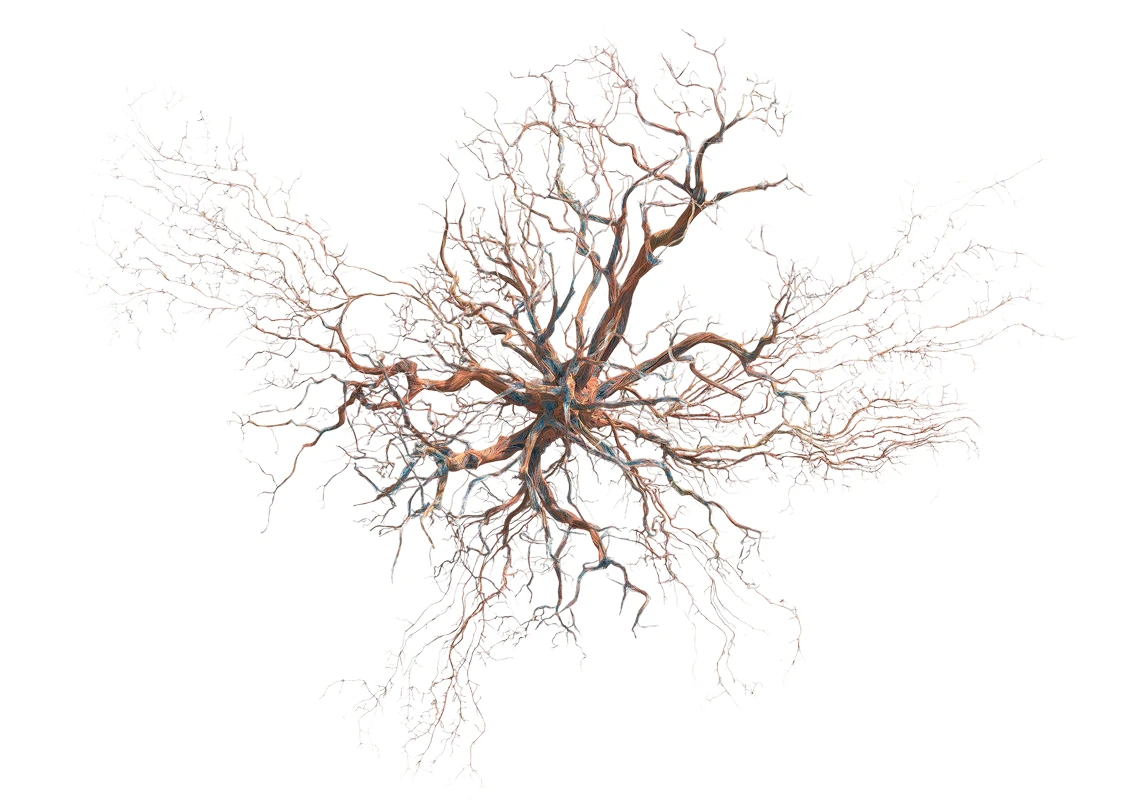

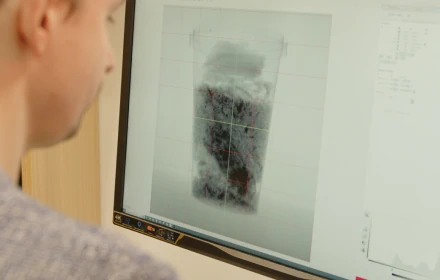

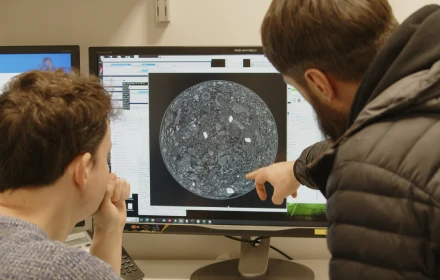

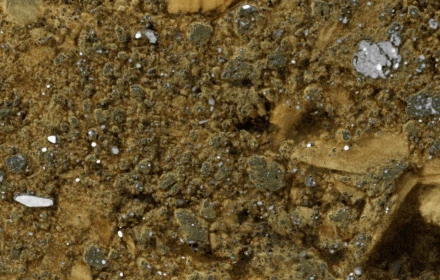

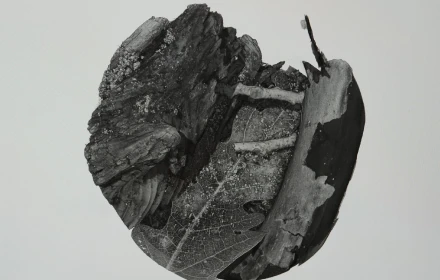

Making of the Artwork Creating a Digital Twin Lidar Scanning Process  In creating Of the Oak, we used advanced tools to reveal parts of the tree beyond human sight. Techniques – including photogrammetry (stitching together thousands of images), LiDAR scanning (mapping the tree’s form with laser pulses) and CT scanning of soil samples – reveal hidden worlds both above and below ground. Ground-penetrating radar traces the oak’s intricate root network, while a series of 24-hour live sound recordings, supported by Kew’s specialist Tree Gang, brings its vibrant soundscape to life.

In creating Of the Oak, we used advanced tools to reveal parts of the tree beyond human sight. Techniques – including photogrammetry (stitching together thousands of images), LiDAR scanning (mapping the tree’s form with laser pulses) and CT scanning of soil samples – reveal hidden worlds both above and below ground. Ground-penetrating radar traces the oak’s intricate root network, while a series of 24-hour live sound recordings, supported by Kew’s specialist Tree Gang, brings its vibrant soundscape to life.

In creating Of the Oak, we used advanced tools to reveal parts of the tree beyond human sight. Techniques – including photogrammetry (stitching together thousands of images), LiDAR scanning (mapping the tree’s form with laser pulses) and CT scanning of soil samples – reveal hidden worlds both above and below ground. Ground-penetrating radar traces the oak’s intricate root network, while a series of 24-hour live sound recordings, supported by Kew’s specialist Tree Gang, brings its vibrant soundscape to life.

In creating Of the Oak, we used advanced tools to reveal parts of the tree beyond human sight. Techniques – including photogrammetry (stitching together thousands of images), LiDAR scanning (mapping the tree’s form with laser pulses) and CT scanning of soil samples – reveal hidden worlds both above and below ground. Ground-penetrating radar traces the oak’s intricate root network, while a series of 24-hour live sound recordings, supported by Kew’s specialist Tree Gang, brings its vibrant soundscape to life. LiDAR scanning is a remote sensing technology that uses laser pulses to measure distances, creating detailed, three-dimensional maps of environments with precision. By emitting rapid laser beams and analysing their reflections, LIDAR can capture intricate structures of landscapes, forests, and architectural sites, revealing hidden details often invisible to the naked eye. Creating a Digital Twin Lidar Scanning Process

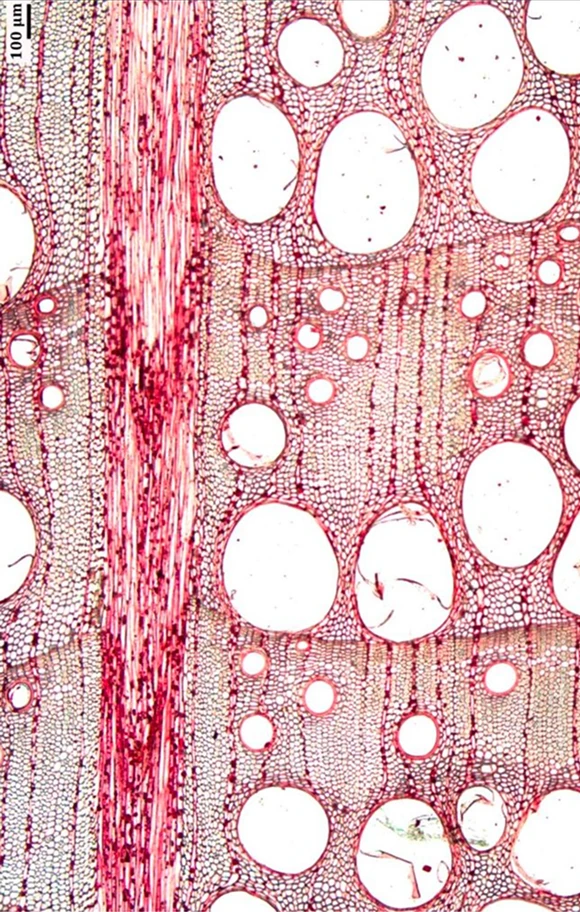

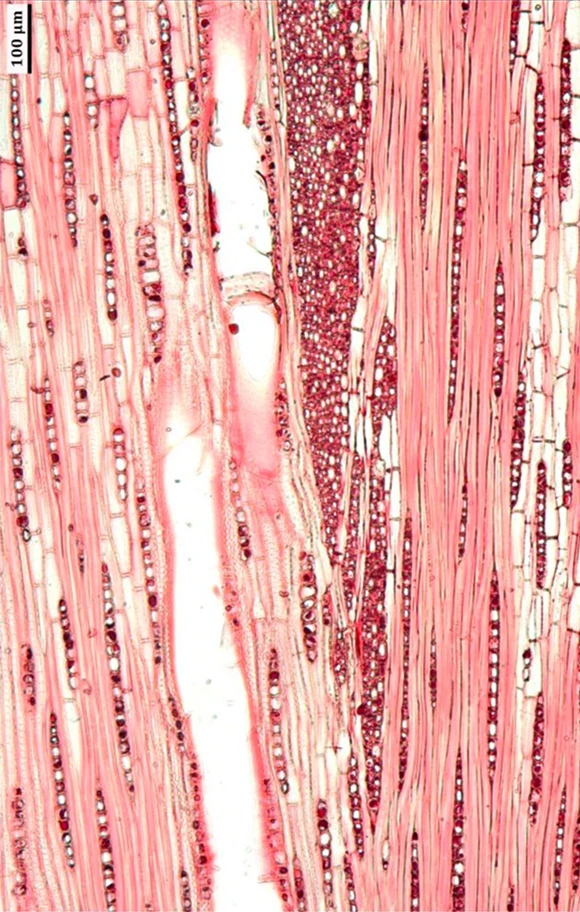

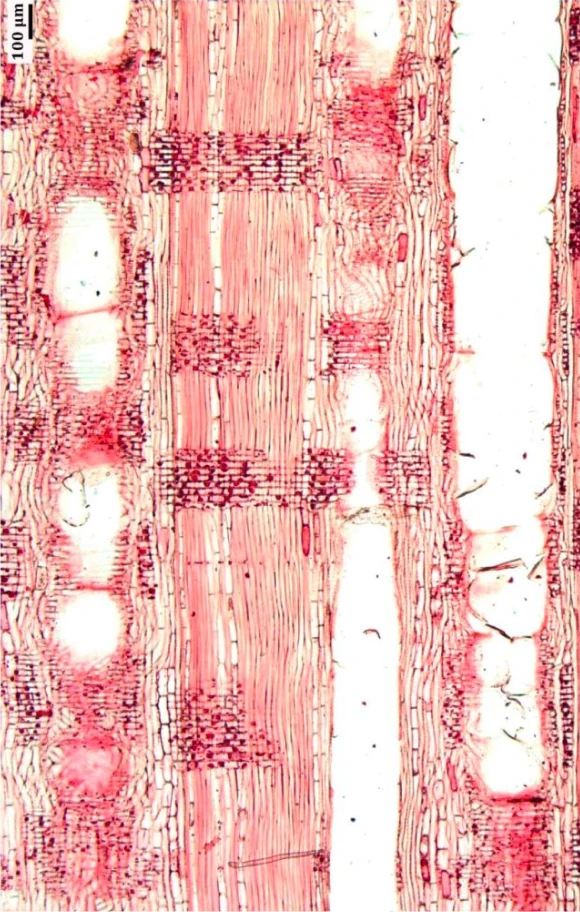

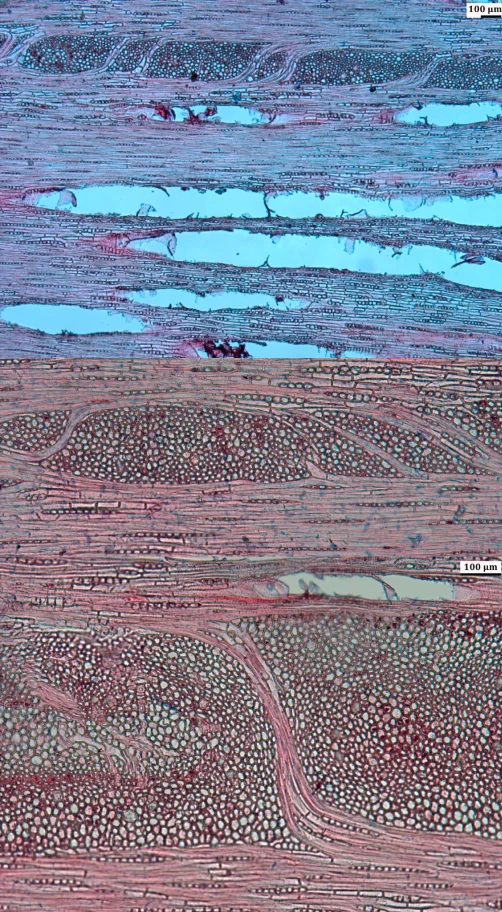

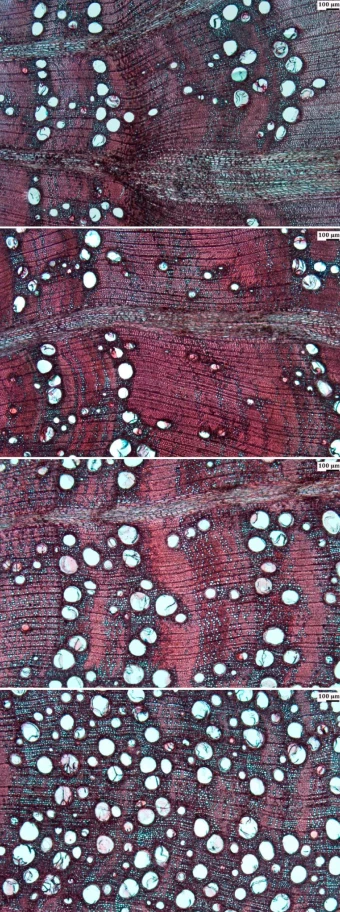

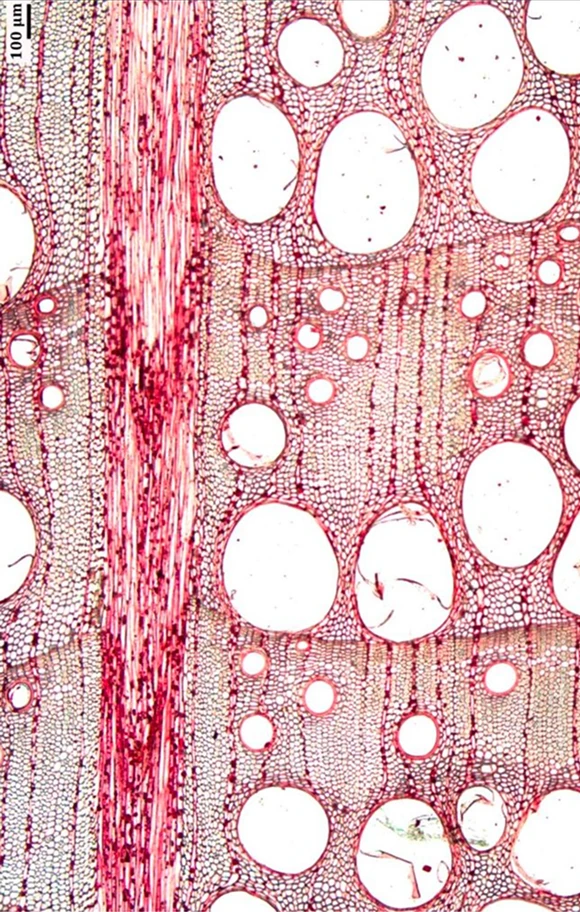

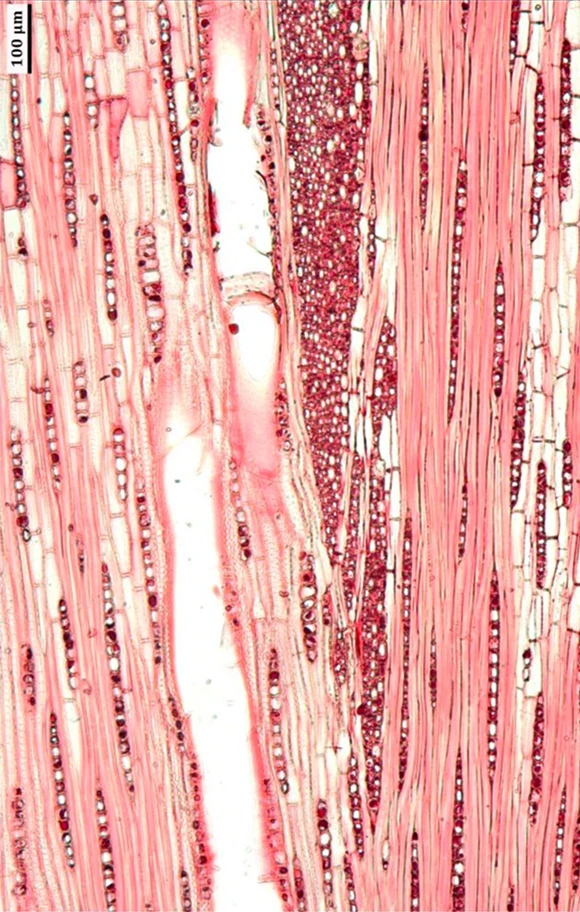

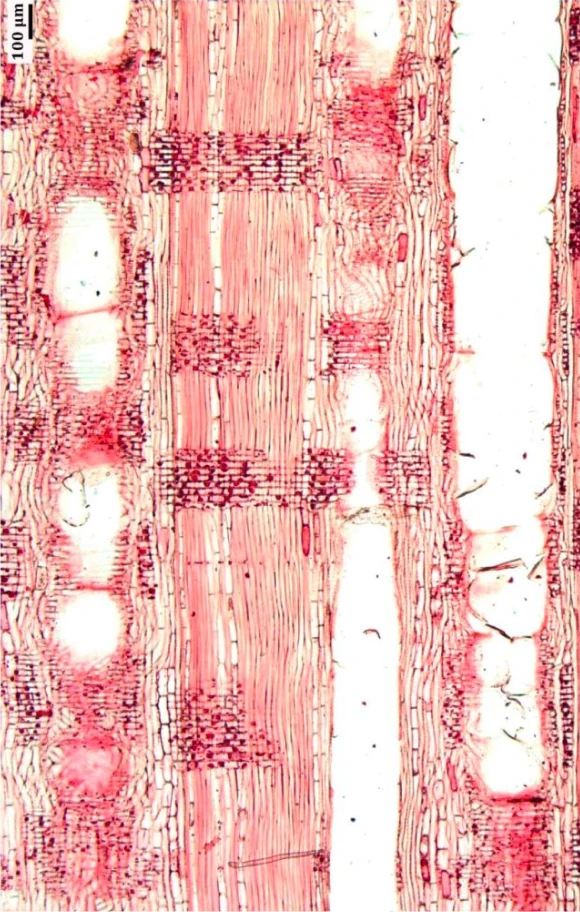

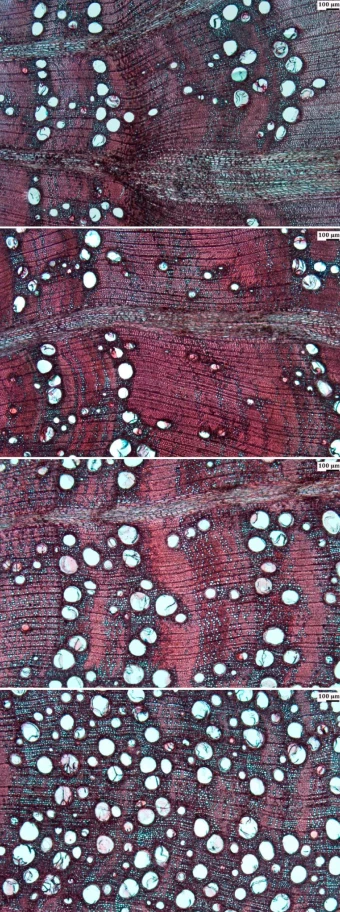

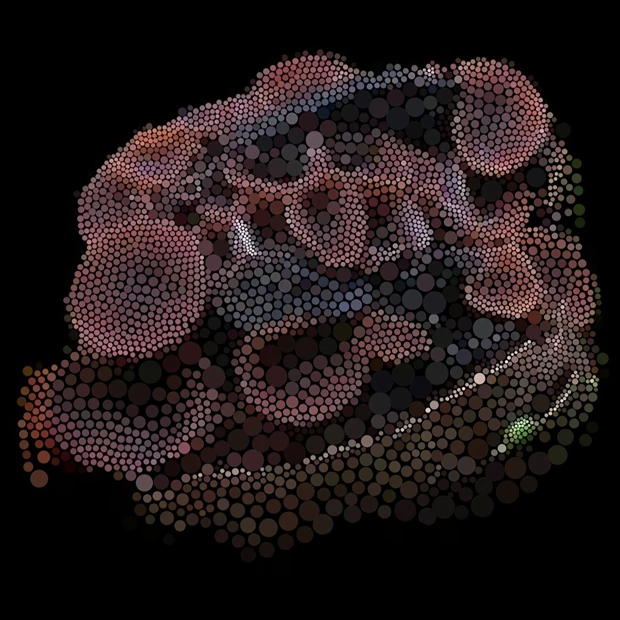

Wood Tissue Studies for Phloem and Xylem construction

Wood Tissue Studies for Lucombe oak conducted by RBG Kew researcher Dr Peter E Gasson

Wood Tissue Studies for Lucombe oak conducted by RBG Kew researcher Dr Peter E Gasson

Wood Tissue Studies for Lucombe oak conducted by RBG Kew researcher Dr Peter E Gasson

Wood Tissue Studies for Lucombe oak conducted by RBG Kew researcher Dr Peter E Gasson

- Ground Penetrating Radar Process Ground Penetrating Radar (GPR) technology is used to peer beyond what is visible to the human eye, revealing the intricate systems that sustain the oak’s body. By transmitting radio waves into the soil and analysing their reflections, GPR constructs detailed, three-dimensional maps of the oak’s root system as it extends deep into the earth – drawing water, absorbing nutrients and forming vital subterranean connections.

- Ground Penetrating Radar Process This process unveils the oak as more than a towering presence above ground; it reveals a vast, interconnected organism below the surface. The roots, like neural pathways, thread through layers of soil and stone, navigating darkness in search of sustenance and stability.

- Root structures What emerges is a portrait of the tree as both anchor and conduit – its underground architecture mapping a hidden world of interconnectedness.

- Soil, fungi & leaf CT scans at Natural History Museum High-resolution CT scanning is used on soil samples to reveal their internal structures in extraordinary detail. This process allows for the visualisation of root architecture, soil composition, and the microhabitats within – offering insights into the hidden ecosystems that support plant life, including the oak.

- Field Recording Process.

To capture the sonic world around the oak. Composer and spatial audio artist James Bulley, in collaboration with the Tree Gang at the Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew, is setting up a multichannel microphone array designed to capture rich tapestry of life around the oak. From the creak of branches swaying in the wind to the gentle rustle of leaves, from the subterranean murmurs of root systems to the bustling activity of creatures that inhabit its bark, this setup seeks to reveal the oak’s sonic landscape.

The recordings aim to create an immersive soundscape that allows audiences to listen deeply to the oak’s presence – its respiration, its resonance and the countless interwoven relationships it sustains.

- Gallery of Sketches, Making of the Oak.

Species of the Oak

Oaks thrive in diverse habitats—from single trees in farmland to ancient Atlantic oak woods. But their longevity is key; older oaks accumulate more species over time, making them ecological anchors. Dr. Ruth Mitchell

Species of the Oak  Symbionts of the Oak Why Are Trees Essential to Life? Trees matter not only for their grandeur, but for their generosity. They are not solitary beings but living systems that nurture entire ecosystems. An oak, for example, can sustain over 2,300 species – offering food, shelter and a web of vital connections. Trees breathe, exchange nutrients, and communicate with their surroundings. Their existence is a quiet yet profound embodiment of reciprocity and resilience.

Symbionts of the Oak Why Are Trees Essential to Life? Trees matter not only for their grandeur, but for their generosity. They are not solitary beings but living systems that nurture entire ecosystems. An oak, for example, can sustain over 2,300 species – offering food, shelter and a web of vital connections. Trees breathe, exchange nutrients, and communicate with their surroundings. Their existence is a quiet yet profound embodiment of reciprocity and resilience.

What Is Our Relationship to Trees? The air they exhale becomes our breath. Their branching roots mirror the networks within our own bodies. We are bound by the same cycles of giving and receiving, woven into a shared fabric of life. Recognising this kinship dissolves the illusion of separateness, reminding us of the essential relationships that sustain all living beings.

The inspiration for Of The Oak began with a startling realisation: just how many species depend on oak trees to survive. In 2019, a team led by Dr Ruth Mitchell published a comprehensive study titled OakEcol: A database of oak-associated biodiversity within the UK. The research catalogued over 2,300 species – including birds, bryophytes, fungi, invertebrates, lichens and mammals – that rely on native UK oaks (Quercus petraea and Quercus robur) for their ecological functions. This study revealed the oak's status as a keystone species – its body not simply its own, but a foundation for countless others.

Within Of The Oak, the species exploration only begins to scratch the surface of these vast, interdependent networks. As we deepen our understanding, it becomes clear: an oak is never truly alone. It is a living world, a pillar of biodiversity whose influence extends far beyond what is visible.

Yet today, as the health of oaks declines under the pressure of pests, disease and climate change, we are called to ask: what is at stake when such a species falters? What else falls with it? The oak stands as a testament to endurance and entanglement – a vital thread in the tapestry of life we cannot afford to unravel. Mitchell, R.J., et al. (2019). OakEcol: Oak-associated biodiversity in the UK.

Symbionts of the Oak Why Are Trees Essential to Life? Trees matter not only for their grandeur, but for their generosity. They are not solitary beings but living systems that nurture entire ecosystems. An oak, for example, can sustain over 2,300 species – offering food, shelter and a web of vital connections. Trees breathe, exchange nutrients, and communicate with their surroundings. Their existence is a quiet yet profound embodiment of reciprocity and resilience.

Symbionts of the Oak Why Are Trees Essential to Life? Trees matter not only for their grandeur, but for their generosity. They are not solitary beings but living systems that nurture entire ecosystems. An oak, for example, can sustain over 2,300 species – offering food, shelter and a web of vital connections. Trees breathe, exchange nutrients, and communicate with their surroundings. Their existence is a quiet yet profound embodiment of reciprocity and resilience.What Is Our Relationship to Trees? The air they exhale becomes our breath. Their branching roots mirror the networks within our own bodies. We are bound by the same cycles of giving and receiving, woven into a shared fabric of life. Recognising this kinship dissolves the illusion of separateness, reminding us of the essential relationships that sustain all living beings.

The inspiration for Of The Oak began with a startling realisation: just how many species depend on oak trees to survive. In 2019, a team led by Dr Ruth Mitchell published a comprehensive study titled OakEcol: A database of oak-associated biodiversity within the UK. The research catalogued over 2,300 species – including birds, bryophytes, fungi, invertebrates, lichens and mammals – that rely on native UK oaks (Quercus petraea and Quercus robur) for their ecological functions. This study revealed the oak's status as a keystone species – its body not simply its own, but a foundation for countless others.

Within Of The Oak, the species exploration only begins to scratch the surface of these vast, interdependent networks. As we deepen our understanding, it becomes clear: an oak is never truly alone. It is a living world, a pillar of biodiversity whose influence extends far beyond what is visible.

Yet today, as the health of oaks declines under the pressure of pests, disease and climate change, we are called to ask: what is at stake when such a species falters? What else falls with it? The oak stands as a testament to endurance and entanglement – a vital thread in the tapestry of life we cannot afford to unravel. Mitchell, R.J., et al. (2019). OakEcol: Oak-associated biodiversity in the UK.

A tree is never alone. It is a porous body, woven from countless threads of connection. When an oak vanishes, it is not just the loss of a tree, but the unravelling of a living network. To truly see a tree is to recognise its role in the fabric of life – sustaining the planet, its creatures, and us within it. Marshmallow Laser Feast

The Future of the Oaks The story of the oak is inseparable from our own. Flint axes once split their trunks to fuel fires that held back the chill of glacial nights. As wildwood was cleared to make space for crops and settlements, the oaks remained – steadfast and essential. Their timber-shaped the structures we called home, while their acorns fed both people and animals through lean seasons. Traces of acorn flour, used as sustenance, have been uncovered across ancient European settlements – a quiet testament to the oak's generosity.¹

Britain is home to more ancient oaks than all EU nations combined,² their towering presence echoing through our culture, economy and landscapes. But beyond their symbolic weight, oaks are living strongholds of biodiversity, supporting thousands of species –from birds and butterflies to fungi and lichens.

Now, these long-standing keepers of life are under growing threat. Oak trees face a convergence of pressures: rising temperatures, shifting rainfall patterns, invasive pests and emerging diseases – all made more intense by a rapidly changing climate. These aren't isolated incidents but layered stresses that weaken the trees' natural defences and disrupt the delicate ecosystems they sustain.³

What has endured for millennia – surviving storms, nourishing life and shaping landscapes – is now standing on uncertain ground. The loss of even a single mature oak ripples outward, disturbing the intricate web of species that rely on its presence for food, shelter and stability.⁴

Protecting the future of oaks means moving beyond admiration into action. We are called not only to understand the oak's ecological role more deeply, but to act collectively and decisively –through conservation, regeneration and long-term thinking.⁵ The oak is more than a tree. It is a cornerstone of life, and one we cannot afford to lose. 1. Mitchell, R.J. et al Oak-associated biodiversity in the UK (OakEcol) 2. Action Oak. 2024. Action Oak Report 2023–24 3. Martin, K. (2025, April 17). Interview with Kevin Martin... 4. A contemporary assessment of the biodiversity benefits... 5. Action Oak. (n.d.). Projects. Action Oak

Britain is home to more ancient oaks than all EU nations combined,² their towering presence echoing through our culture, economy and landscapes. But beyond their symbolic weight, oaks are living strongholds of biodiversity, supporting thousands of species –from birds and butterflies to fungi and lichens.

Now, these long-standing keepers of life are under growing threat. Oak trees face a convergence of pressures: rising temperatures, shifting rainfall patterns, invasive pests and emerging diseases – all made more intense by a rapidly changing climate. These aren't isolated incidents but layered stresses that weaken the trees' natural defences and disrupt the delicate ecosystems they sustain.³

What has endured for millennia – surviving storms, nourishing life and shaping landscapes – is now standing on uncertain ground. The loss of even a single mature oak ripples outward, disturbing the intricate web of species that rely on its presence for food, shelter and stability.⁴

Protecting the future of oaks means moving beyond admiration into action. We are called not only to understand the oak's ecological role more deeply, but to act collectively and decisively –through conservation, regeneration and long-term thinking.⁵ The oak is more than a tree. It is a cornerstone of life, and one we cannot afford to lose. 1. Mitchell, R.J. et al Oak-associated biodiversity in the UK (OakEcol) 2. Action Oak. 2024. Action Oak Report 2023–24 3. Martin, K. (2025, April 17). Interview with Kevin Martin... 4. A contemporary assessment of the biodiversity benefits... 5. Action Oak. (n.d.). Projects. Action Oak

When we think about climate change in the UK, we have to understand that it won’t affect all regions the same way. The south-east is getting hotter and drier, while the north-west is becoming warmer and wetter. If we don’t manage it, trees will naturally begin to migrate – moving north and west over time – because that’s where the better growing conditions will be. But in the south-east, where most of our population lives, we’ll see native species such as oaks struggle and disappear. That’s why it’s so important to act now, to understand what’s coming, and manage that transition with care and strategy. Kevin Martin, Head of Tree Conservation at Kew

Resources & Call to Action

Books: Oak, The Frame of Civilization by William Bryant Logan Oaklore by Jules Acton Oak by Peter Young Descriptions and Sketches of Some Remarkable Oaks by Hayman Rooke Oak by Katharine Towers The Oak Papers by James Canton Oak Tree, Natural History by Richard Lewington The Natural History of Blenheim High Park by Aljos Farjon The Lost Rainforests of Britain by Guy Shrubsole The Glorious Life of the Oak, by John Lewis-Stempel Online Resources: A Legacy of Ancient Oaks by Marc Frith International Oak Society Research: Oak-associated biodiversity in the UK (OakEcol) FUTURE OAK is a pioneering project investigating the role of beneficial microbes in fighting diseases that affect the Britain's native oak trees Collapsing foundations: The ecology of the British oak, implications of its decline and mitigation options Call to Action: Support Kew Gardens Join RBG KEW in their mission to fight biodiversity loss and climate change. Support the Action Oak Initiative Join a coalition of charities, landowners, and scientists working to protect the UK's 121 million native oaks from pests, diseases, and climate threats. Plant Native Oaks with the Woodland Trust Get involved in tree planting efforts to restore native oak woodlands across the UK. Report and Monitor Ancient Trees Help safeguard ancient oaks by recording them in the Ancient Tree Inventory, aiding in their protection and study. Advocate for Stronger Tree Protection Laws Support campaigns calling for enhanced legal protections for ancient and veteran trees, ensuring their preservation for future generations. Engage with the Heart of England Forest Participate in large-scale reforestation projects focusing on native species like oaks to rebuild England's woodland heritage. Engage with the International Oak Society Join a global community dedicated to the study, conservation, and appreciation of oak species worldwide. Become aware of the Lost Rainforests of Britain

Credits

An Artwork by Marshmallow Laser Feast: Ersin Han Ersin Barnaby Steel Robin McNicholas Commissioned by: Royal Botanic Gardens Kew Executive Producers: Eleanor (Nell) Whitley Mike Jones Producer: Roxie Oliveira Head of Studio: Sarah Gamper Marconi Lead Artist: Quentin Corker Marin Lead Creative Technologist: Chris Mullany Creative Developer: Sam Twidale VFX Artists: Nicolas Le Dren Lewis Saunders Technical Lead: Miryana Ivanova Music, Sound Design: James Bulley Sound System Engineer: Simon Hendry Assistant Recordist: Jake Tyler Richard Hards Recording Musicians: Kat Tinker Audrey Riley Daniel Pioro Ian Stonehouse Graphic Designer: Patrick Fry Researcher, Copywriter: Eliza Collin Marketing and Communications Lead: Erin Wolson Technical Studio Assistant: Ieva Vaitiekunaite Studio Administrator & Production Assistant: Alex McRobbie Online Field Guide Design and Development: Lusion Lidar Technician: Zachary Mollica PR: Margaret Contributing Authors for Meditations: Daisy Lafarge Merlin Sheldrake Laline Paull Ella Saltmarshe Meditations Voiced by: Michelle Newell Merlin Sheldrake Scientific Advisors & Contributors: Kevin Martin (RBG Kew) Justin Moat (RBG Kew) Dr. Laura Martinez-Suz (RBG Kew) Lee Davies (RBG Kew) Peter Gasson (RBG Kew) Dr. Ruth Mitchell Prof. James McDonald Dr. Jenni Stockan Paul Bellamy - (RSPB)

For Marshmallow Laser Feast Executive Producers: Alex Rowse Carolina Vallejo Senior Producer: Martin Jowers Producers: Anya Tye Emmanuel Adanlawo Tools & Infrastructure Engineer: Maria Astakhova

Contact General Enquiries oftheoak@marshmallowlaserfeast.com Press Enquiries Louise@marshmallowlaserfeast.com